BY RUBY BROOKE

“I think with great artists and great geniuses like Rimbaud, their whole life is their art and you can’t distinguish between one and the other”

Karen Strang doubts she’ll ever retire, and I’m not sure she could if she wanted to – the paint seems to be flowing out of her fingertips. She graduated from the Glasgow School of art in 1985, and has won numerous prizes since then, as well as exhibiting her work in galleries across the globe – including Poland, the USA and her native Scotland. Her paintings bleed with vivid colours that drip down their canvases, providing the vibrant backdrop for her fluent squiggles of colour and examinations of nude bodies and bare faces. For years now, she’s been translating her emotions into tangible images: from heads adorned with horns and flower crowns in her exploration of the female gaze within myth (exhibitions ‘Syrena’ and ‘Succubus’), to her foregrounding of the importance of community in the era of COVID (exhibitions ‘Heroes Here & Now’ and ‘Look Aboot Ye’). I was able to meet with Karen via Teams to discuss one of her earlier exhibitions ‘Illuminations 1874’, in which the painter retells the myth of ‘poète maudit’ Arthur Rimbaud through 12 paintings of the sketches and images generated whilst he was alive. Karen invited me into her very own Rimbaudian shrine, equipped with a lifelong fan’s collection of paintings, sketches and memorabilia as well as a copy of Illuminations so dearly loved, it was falling apart at the seams. Read along for a passionate discussion of what makes a true ‘voyant’, Rimbaud’s androgynous persona as well as tackling the struggles of being recognised as a female artist, as we chase down the myth that is Rimbaud – right until he walked himself to death.

BROOKE: I think Rimbaud has this indescribable allure, it's like once you pick him up you know you've found magic. In Just Kids, Patti Smith describes picking up a book of his and just instantly falling in love with the picture of him on the back. So, where did your love affair with Rimbaud begin? And how did he come to inspire your 2014 exhibition 'Illuminations 1874'?

STRANG: I've called myself a feminist from the beginning. And I grew up when, well we're not equal now either, but it was certainly more difficult back then. So I discovered Rimbaud when I discovered punk, really. I was always into my art and I love art history as well. I loved reading about my favourite artists, Degas and Manet. The French artists were actually really political, people think of them as being very chocolate-boxy, but actually they were the first group of people in France to paint the French proletariat. The workers at leisure. So, you have painters like Seurat as well who invented, let's say, the pointillist process. A lot of the time, with this emergence of the middle classes, they also had women being more connected to society as well as men were. So for me, it was about showing women as well - working women, as well as on the streets, or women who now could have a sense of agency and autonomy with their own wealth to some extent. So, I'm wearing the top hat because Rimbaud wore a top hat. But it's also been seen as a masculine thing, and it doesn't have to be. So, around the time Rimbaud was writing you had artists like Manet who painted a fantastic portrait of a woman called L'Amazon, and she's actually a horse woman. If you look at the painting, you'll see that I'm dressed a bit like her, without the flowers. That's the poetic touch. And that's the idea behind wearing masculine attire.

BROOKE: That's gorgeous.

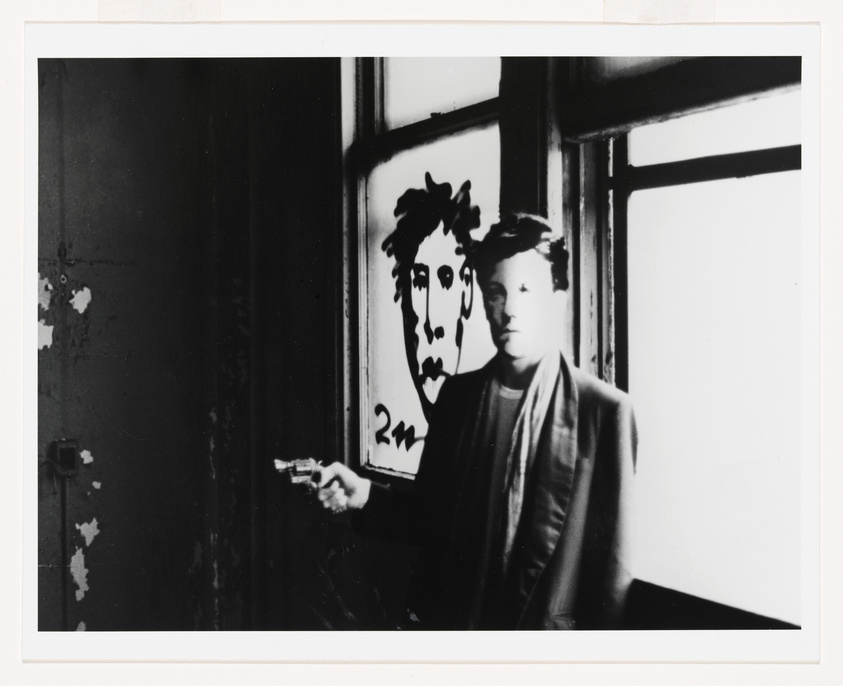

STRANG: So, you have people like George Sand, who was Chopin’s mistress and also collaborator. In the 1860s, she was wearing what’s considered male attire. So I thought the top hat references a lot of things. I got into Rimbaud through music as well, and he was just kind of in the ether, he was just one of those names that would keep reappearing. But still very niche. Still not somebody that most people knew. I’m going to show you a picture of me when I was 19 and it’s quite spooky.

BROOKE: Oh, that hair is great.

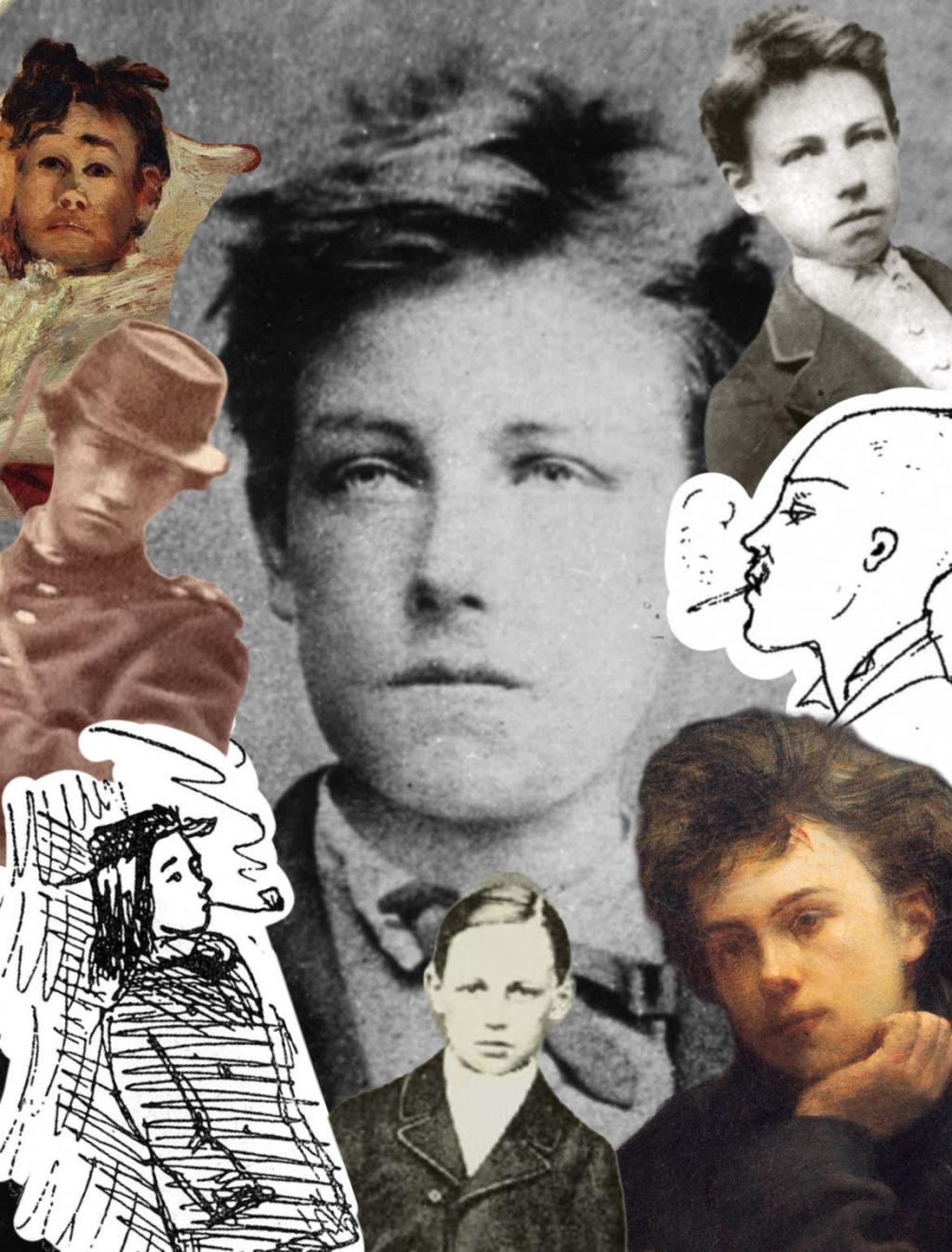

STRANG: That’s me at art school. I’m a painting student at that point. Now, I was somewhat aware of the Fantin-Latour portrait of Rimbaud, but honestly, this spooked me out because I only came across this much later. There’s Rimbaud and there’s me.

BROOKE: That’s crazy. That’s uncanny.

STRANG: I didn’t pause to look like Rimbaud. I just paused to look like me. It’s weird, isn’t it?

BROOKE: That’s so funny. You’ve got the gaze perfectly too, the gazing off into the distance. That brings me onto my next question actually, there’s a really limited amount of pictures of Rimbaud. The most famous one is probably his studio portrait at 17, where he’s tight-lipped and gazing off into the distance. This image has become almost commercialised in a sense, David Wojnarowicz has a series of photographs called Arthur Rimbaud in New York where he photographs a lone figure in this Warhol-esque mask of Rimbaud. What was it like to tackle this notorious concept of Rimbaud by painting in the rest of his story?

STRANG: So, when I started doing this project, I’d been going through quite heavy cancer treatment. So I started to reintroduce myself to Rimbaud whilst i was coming through chemotherapy and then that got me interested in examining what Rimbaud was about and I had a lot of time on my hands at that point. And then as I was emerging and hoping to get back into painting as a practice again, I applied for a research travel grant so that I could go to Charleville, the place Rimbaud was born, and from there I had this idea. I had to have an idea for a project and at that time there was only maybe 12 or 13 actual images of Rimbaud in existence. I think there’s a question mark over another one since them I’m aware of, of him during the Paris Commune as a soldier. I can’t say for sure if it’s Rimbaud or not. It’s a difficult one, but I guess it’s like gold dust. It’s one of those things, like the holy grail. Someone is, including myself, on the search to find this image of Rimbaud. This is before the internet really started to take off, around 2010. So there were images but they were quite crudely represented, so you had to look in books which was great. And I basically exhausted the research to find these images. And I got all the images that anybody else could get. The problem now is that it’s so easy to get deep fakes. There’s a lot out there and it’s kind of sad that some are so good that people think ‘Oh, this is actually Rimbaud’ and it’s not. But if you’re doing this as an artwork or you’re doing it with the conceit of specifically pointing it out, there’s not an issue. I don’t have a problem with somebody as an artist saying ‘I’m going to project Rimbaud on a wall’, or ‘I’m going to project Rimbaud into another situation’. I couldn’t see anything against that and that’s kind of what I was doing, I was putting myself into the position of Rimbaud too. I thoroughly enjoyed the research looking for these images and I found that challenge really stimulating. But, also at that time you couldn’t really animate those images except through old school style film animation. And I thought, ‘What can I do as a painter to provoke a response from the viewer so they can see another aspect of Rimbaud?’. And it’s a very visual thing, painting – it’s not about how he sounds, it’s not about how you read him. But saying that, obviously I had to get into the whole language of his, and I don’t just mean the French language, I mean his personal language. Although I’m a visual artist, I have done a bit of performance art before and for me it’s quite performative as well. Connecting Rimbaud with what I do there’s also the aspect of synesthesia, I think of Rimbaud as possibly being a synesthetic person. And I think painters are too, I could visualise a lot of the sounds. The thing about synesthesia is it’s about your perception of things. I liked your theme about the ‘systematic derangement of the senses’, which is really where all the senses start to explode and implode and change and juxtapose and that’s a very punk way of thinking. Well, if you look at the first wave of punk, it was about dissembling things and dissonance and really pulling apart things to recreate them. If you think of Jamie Reid’s iconic graphics on the Sex Pistol‘s album where he cuts up newspapers and sticks them on and makes them something else. I think Rimbaud was kind of doing that with his words. He’s cutting out things and sticking them in a way that’s like a collage. But also breaking up the norm, breaking up the established form. You’re really smashing the establishment by doing that.

BROOKE: Right. It’s interesting you suggest Rimbaud could have been synesthetic, especially considering his poem Vowels where he’s assigning colours to the vowels.

STRANG: (She holds up a miniature artwork made up of clipped out vowels of different fonts and sizes) This is my little versions of those. As you know, he transposes the ‘u’ and the ‘o’ so it reads like it’s normal until you realise it’s the wrong way around. And what I’ve done here is I’ve used different types of lettering, some of them are contemporaneous from Rimbaud’s time, so you’re talking about typography from the 1870s. And actually the graphics from the 1870s are quite modernist sometimes as well. This was quite synesthetic for me because obviously the shapes of the letters jump out at you and each shape of the letter can have a sound, but can also have a colour. But also when you actually say them, the way that you pronounce these phonetically, they sound quite weird and animalistic and wild and savage.

BROOKE: That’s so interesting how you link that to the idea of collaging. With his theory of the ‘systematised derangement of the senses’, do you think this is just something Rimbaud practised in his writing, or in his real life too? He lived a tumultuous, tortured life. Do you think there’s an element of him seeking that out, of artists longing for experiences of a heightened reality? I think there’s always this idea that artists have to have these great experiences.

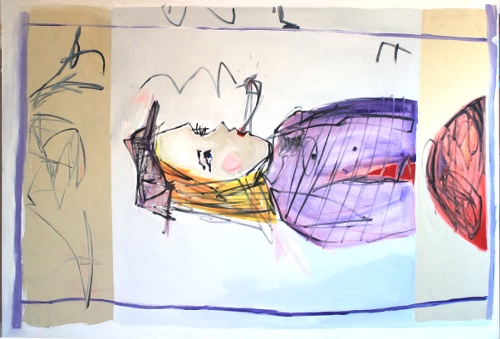

STRANG: I think with great artists and great geniuses like Rimbaud, their whole life is their art and you can’t distinguish between one and the other. But, he did so much in that very short period. He lived until he was in his 40s, but really his life as an artist stopped by the time he was 21. His mean output was between the ages of 14 and 18. That’s his phrase, isn’t it? ‘I’ve seen it all, I’ve done it all, I’ve heard it all’. He’s exhausted by it. He’s done with it. He has lived a full life in what people may take another 60 years to do, it’s fascinating. But I think he had a very difficult time, absolutely, and he embraced the challenges. But I don’t think he shied-away from them either. We’re only left with his words at the end of the day, these sort of fragments of his life and images. We’ve got some sketches as well that were done by his friends, my painting Drunken boat is based on a sketch Verlaine did of Rimbaud.

BROOKE: Right, I noticed that.

STRANG: And I turned it on its side, so it was like a boat. When the two came over to England, I get the impression they had a rocky journey on the sea. And they did it a couple of times and they had a very tumultuous relationship and a very difficult one. But what I think is amazing is how this young sort of schoolboy managed to attract the attention of this very well regarded and established writer who was a married man with children. And he just made him go to a completely other way of living. Apparently, Verlaine was attracted to his eyes. To understand Rimbaud, in a way, you have to read Verlaine at that time too, because Verlaine was completely besotted by Rimbaud. Which is so odd and unusual, how that could turn that way round. So you read how he talks about Rimbaud’s blue eyes. That’s a trope I’ve put into some of the works I’ve done. Rimbaud’s eyes.

BROOKE: You mentioned earlier Rimbaud’s quote, how did you translate it? ‘I’ve done it all’.

STRANG: (She picks up a copy of Rimbaud’s Illuminations, so well-loved it’s falling apart at the seams) So, in the best Rimbaudian style, this is a version of his Illuminations. And what I do is I translate them into Scots. You know, all the Illuminations were found in sheets, so somebody had to try and put them back together. It’s like he’s actually done this with this book, he’s mixed them all up. So the poem that quote is from is Departure: ‘Seen enough. The vision appeared in all atmospheres. Had enough. Uproars of the cities in the evening, and in the sun, and always. Known enough. The impasses of life, our uproars and visions. Departure in new affection and new glamour.’ This is one of his very last pieces, although we don’t know if it was the last piece in the Canon of Illuminations. But generally speaking, that was near the end. Because once you’ve done it, what do you do?

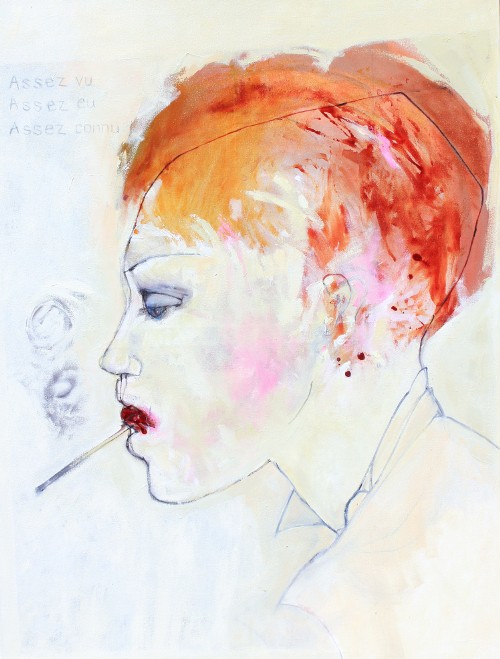

BROOKE: He sounds resigned, which is so uncharacteristic of Rimbaud. Was that poem the inspiration for your piece Assez vu?

STRANG: Yes, absolutely. that’s the original phrase in French.

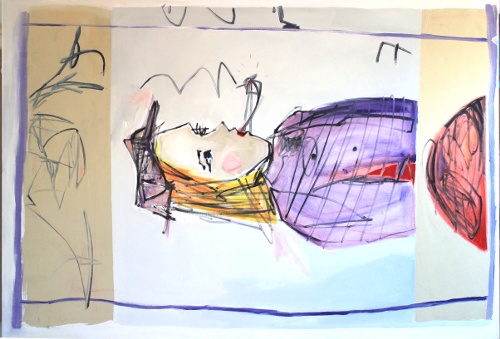

BROOKE: Right, that painting was really the standout piece to me. Your Rimbaud is pale, washed out and turned away. His youthful hair is now fiery red, as if marked by blood. Did you feel particularly impacted by his abandonment of his art?

STRANG: I think he did a very brief thing, but a very true thing. He was true to himself. I think it was possibly creative burnout. I think he experienced and expressed beautifully, these things in a very youthful, energised way. It couldn’t be repeated into mature age. It was as it was and I think he could only leave because he had done what he set out to do. I think he came to the point where that was it. And the second-half of Rimbaud’s life was entirely different from his first, he becomes a gun runner and lives a totally different life and he walks himself to death, literally. People say, ‘but how did he really die?’ He walked himself to death. They brought him back, dying to Marseilles and then he was buried in Charleville. I think he had gangrene in his leg. He just tired his legs out. It’s just a ridiculous way to go, but at the same time kind of understandable. He had this energy still within him, but it obviously became just this physical energy towards the end because he didn’t do much in the way of writing after his early 20s. He’s a very different person when you see the photographs of him later in life, it’s very hard to equate that with the young and wild child.

BROOKE: It’s sort of heart-breaking. Verlaine said the ‘very obvious’ reason Rimbaud gave up poetry was because ‘he grew up… the child in him died’. I turn 20 in a few weeks and that terrifies me. What are your thoughts on the concept of a ‘prime artistic period’?

STRANG: I think it’s different for everyone. As a painter and a feminist, I would say that women who are painters have quite a difficult time of things. The patriarchal society doesn’t really give us the opportunity to have a trajectory that flies up into the stratosphere as it does for a lot of male painters. Because generally, there’s discrimination on all levels, but also we are seen as the carers in society. So if we decide to have a family, we’re the ones that stay and look after them, we’ll feel responsible for that. We’re also generally carers for other members of the family. If we’ve got parents, we’re the ones that are expected to put our career aside. There are a number of factors. I think it is improving. I think it’s a lot easier now for women to get into the arts and be treated on the similar level. But as a painter, I think we come into our own. People like Picasso and Matisse were painting well into their 80s. Painters are not poets, and maybe because we have a physical craft we work on we can always learn our craft better as well as develop ourselves intellectually. I think as a female painter, we don’t come into our own until until after the menopause. To be honest with you,

even when we are less discriminated against, post-menopausal women are still ignored or treated as less than. But I would say as a woman painter,

I’m still probably on the career level of a of a 35 year old man who hasn’t had any chase. It’s sad too, but it means when I get up in the morning I feel I’ve got a purpose. I don’t feel like I’ve done it all. You know, it’s unlikely I actually ever retire.

BROOKE: That’s so amazing to hear, especially as someone who aspires to always be developing artistically. It’s really nice to hear you can keep growing and improving and even reach this ‘artistic peak’ later on. I think that’s great.

STRANG: I’m hoping that women of your generation don’t have to wait quite as long as I had to to get my first sort of professional studio. I think life is getting easier, definitely, but it’s not perfect by any means, and there’s still a lot of things that we as women need to sort out and to ensure that we have that parity. Even now, men still command bigger prices for their paintings than women do, which is kind of crazy. I think painting should not be gender based. Anyone can paint if they want to. Rimbaud, for me, talks about women in that very appeal. In the letter to Demeny, he talked about ‘when the eternal slavery of women is destroyed’ which is a very powerful line, and one really worth holding on to because we’re not there yet by any means. You’d think after 150 years, we’d have moved on considerably further. I think Rimbaud spoke to me as a young woman, although he was male, he wasn’t helping construct this patriarchal establishment like so many commentators and writers and well-regarded people in the arts were. 95% of all the people that I studied in painting were men apart from contemporary women. One of my researches at the moment is looking at the women from the 16th and 17th century who were painting and had careers as painters. I think it’s fascinating for a lot of women to know that although we talk about the old masters, there were actually some old mistresses there too. There were women in their studios working. So for me, Rimbaud is kind of a non-gendered voice, he’s talking as a human and I think great art is like that. Rembrandt, the artist’s artist, is considered one of the great painters because he paints from a position of humanity. There isn’t so much a male gaze in his work, he doesn’t objectify women. Likewise with Rimbaud, you can argue there are works which appear specifically to be about a man looking at a woman. But when I look at Illuminations, they’re very clearly for both genders to read. And if you think about the 1870s, this was the height of the gentleman with his cabinet of etchings of naked women, and having a cigar in the smoking room, and having these rather lush images on the walls. This was the time when there was a lot of titillation about women’s bodies. But then, Rimbaud breaks that mould, he really smashes it because he’s not afraid to talk about desire and sexuality. One of Rimbaud’s go-to guys was Walt Whitman, that’s somebody in America doing something similar that was shocking at the time. I think Rimbaud was taking that to a different level because Rimbaud doesn’t just speak to writers. He speaks to musicians, like Patti Smith, and he speaks to visual artists and he speaks to playwrights. He can speak to anybody through his work. When I think about, Tennison or Wordsworth, I’m excited by them but not to the extent I want to paint Wordsworth’s daffodils.

BROOKE: That’s really interesting because I can definitely see the androgyny of Rimbaud in your artwork too, like the colours you choose to paint his face with in Assez vu are almost like makeup.

STRANG: I do think that Rimbaud was an androgynous figure, physically as well as intellectually. I’m not alone with this supposition that he may have been intersex. That’s quite a big thing to throw out there, but I do think he was certainly androgynous. I don’t want to get into gender politics, but I feel he’s not just this male character. He’s something beyond that, he connects with women as much as he does with men.

BROOKE: I’ve honestly never thought of that, but that is such a great observation. What’s the quote he always repeats? ‘I is another’. I wonder if that plays into the idea that he is never one thing.

STRANG: So, in Antique, he says ‘Your heart beats in that womb where the double sex sleeps. Walk at night, gently moving that thigh, that second thigh, and that left leg’. Physically, if you account him as male, he’s still clearly dissociating himself with being male when you read a poem like that. If you read, there are tiny little fragments and you kind of have to read them again and analyse them with some of the biographies. The fact that he goes off radar by the time he’s 21. Well, if you think about it, and this is a huge leap of imagination, by the time you’re 21 you can just about get away without having a beard or facial hair.

BROOKE: Right. And then he went on to lead this sort of ultra masculine, all guns blazing kind of life. So maybe he felt that it was time for him to abandon that sort of androgynous fantasy.

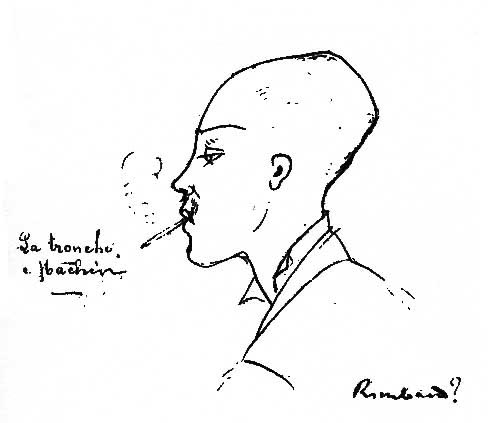

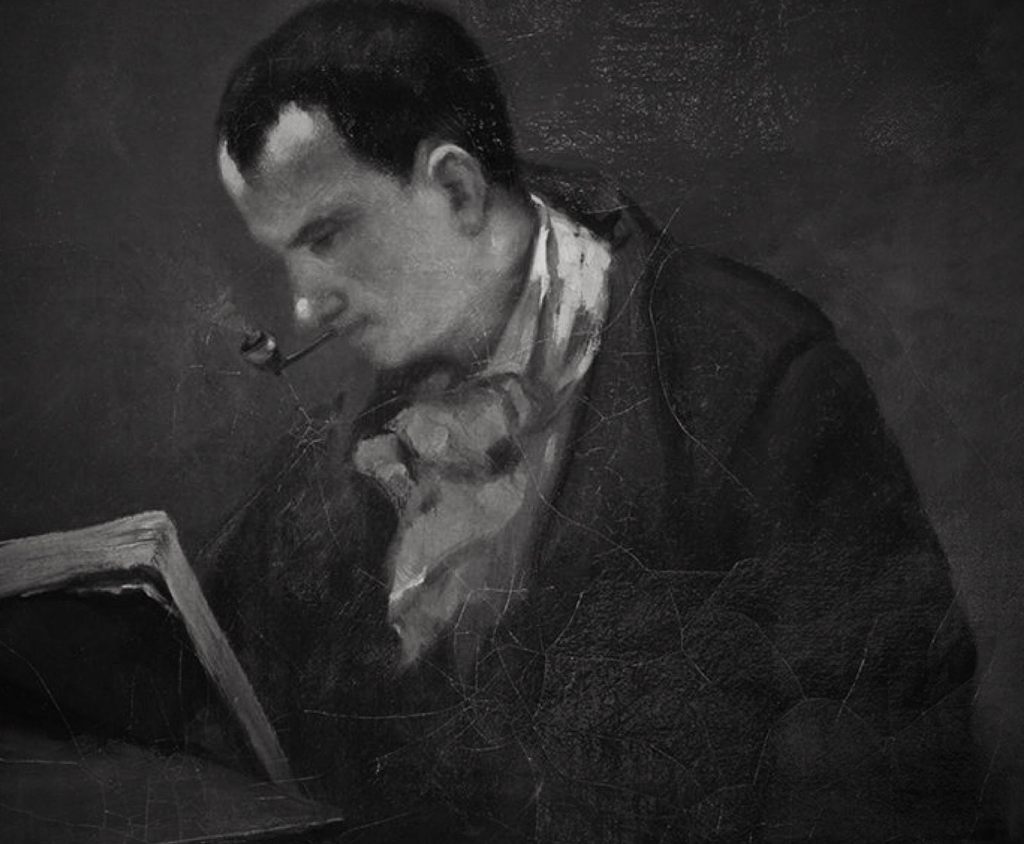

STRANG: He went off and lived a very mysterious life, you know. Nobody really knows a great deal. He left behind all his associates by that time, and he was living in the wilderness. From having been in Paris, in London, you know, Café Society. And then suddenly he just goes away and there’s this very other difficult, different life: a mysterious life as a recluse. You take the facts and then you think, well, why would you do that? So the the painting that you’re thinking of, that’s based on a sketch that was done by his friend Delahaye. And he did this little sketch of of Rimbaud smoking what would have been a very fine rolled up cigarette. The template for the drawing that I created for that canvas is based on this little sketch that was done by his best friend. They’re sitting in the café in Charleville and Rimbaud’s back from all his adventures and thinking ‘What am I going to do next? I don’t know what I’m going to do. I’m going to learn the piano.’ Well, he never does. He ends up going to Aden. So, that’s one of the last conversations he had with his friend before he left Charleville for good. And then off he went. So it’s sad and poignant and fascinating.

Leave a comment