BY RUBY BROOKE

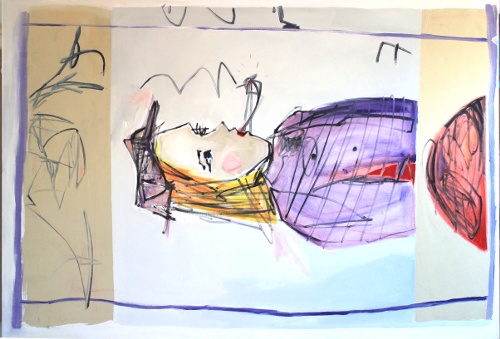

Dr Brian Baker is currently a Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. His creative specialties lie in creating ‘doctored texts’ in the form of erasure poetry. These are multimedia experiments performed on novels featuring expressionist, geometric shapes and beautifully scribbled faces in a haunting, dream-like interpretation of classic novels. Through Baker’s eyes, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde transforms into The Will and H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine morphs to be An Invention. He surgically singles out individual words and phrases so they look you right in the eye, whispering you a haunted story that was previously untapped. To give an insight into the practice of an experienced ‘cut-upper’, I was able to interview Baker on the inspirations behind his work and the future of the method, as well as advice on how to perfect the art of Burroughs’ technique.

BROOKE: So, this month I'm encouraging readers to experiment with Burroughs' cut-up method and also think about the role coincidence plays in everyday life. You've become this master word surgeon of text and collage, perfecting the craft of erasure poetry. Could you summarise your creative journey?

BAKER: Good question. Well, many, many years ago when I was doing my A levels, i was introduced to the work of Tom Phillips, who recently died. He painted prominently in the 60s. He was connected to pop art and pop artists like Richard Hamilton and Peter Blake. He was himself interested in Burroughs and the cut-up, but he wanted to find a different method of doing it. And so, he was kind of rooting around in a bookstore in Camden Town in the 60s. 66. And he came across this novel, this kind of huge Victorian novel called A Human Document by a long neglected author called W. H. Mallock. And he decided, 'I want to do something with this. This looks like it's rich in material to do stuff with', you know, using Burroughs' method. But because he was a visual artist, Phillips decided to take Burroughs' and Gysin's standard method of cutting things up with scissors and use it as an artistic practice instead. To use erasure and to use visual means: painting, collage and other things to do a version of Burroughs' method and use these books and he continued with this project until he died. It was nearly 60 years he was involved in this project called A Humument which has been published in loads of editions. So when I was given this, I was given a video actually by my A level teacher and it blew my mind. I thought 'Wow, this is fantastic', but because I went to university to do English rather than going to art school, it just kind of lay dormant in the back of my mind for a really long time, for decades until I decided in 2018 I really wanted to pursue this. And the text I decided to this with was The Time Machine by H. G. Wells, which is a text I've been interested in for different reasons for quite a long time. And so, I thought, I'm going to take Phillips' method and see how it works in practice and application. And it was really interesting because I found out loads of different things about how different editions of the novel speak to you in different ways. Because different parts of the text appear on the page differently and the layout changes. But also, my method is a bit more narrative than Phillips': whereas his tend to be more page to page with recurring characters, mine tend to be organised in, sometimes a bit oblique, but they tend to have more of a narrative structure.

BROOKE: Yeah, you create these whole new books that you otherwise wouldn't have seen. Do you find it to be a cathartic experience? I mean, there's this odd contradiction in the freedom that can be found in being limited to one text. Do you find the practice helps you work through emotions, or emotions present themselves to you?

BAKER: Yeah, I think that's really interesting. I mean, I've always found Burroughs' approach to text really liberating. That as a reader, it provides you with a kind of agency and the book itself is a bit of a sacred cow, isn't it? You know, some people feel a little bit hesitant at even dog-earring or putting pencil marks in books. One of the first things I did when I started my MA a few years ago, after I started that book, was to get a fire pit and I put a couple of books in it just to see what it felt like to burn them because it is such a sacred cow. It felt horrible. It felt really, really awful and I felt kind of sullied afterwards that I'd actually done it. So I think having that kind of practice, you can come up those things by different means. It does release different things in you and just like my emotional reaction to burning those books, I think you're absolutely right. There is a way in which it puts you in a slightly different place, and that's really important. I think as an artist and a writer, it gives you access to different channels that aren't the ones that are conscious or normal. And Burroughs talks a lot about channels and I can see in terms of the practice, that's kind of what happens. It gives you a different kind of access.

BROOKE: I used to have this whole copy of Walt Whitman's Leaves Of Grass I dedicated entirely to cutting up. I think I have like 3 different copies, but that's a way around the emotional trauma of destroying it.

BAKER: What did you do with it?

BROOKE: Well, I used to do the cut-up method with it, just experimenting, but I haven't touched it in a while actually. So trying out the method again is exciting. There's definitely something to be said about the accessibility of erasure poetry and the way it blurs distinctions between highbrow and lowbrow. Do you view this as a positive for the artistic world?

BAKER: Absolutely, yeah. I mean, one of the things Gysin says is that anyone can do it, it's a democratic method and you don't need technical facilities. It's collage. You don't need to be a great artist or a great painter or have spent years and years perfecting your art to do either of those things. And it's generative. What I like to do with cut-ups is to repeat them. So you cut up a new page, then you stick it back in the process again and it gets more and more strange. But also there's more of your hand on the tiller as well. I think the more times you process it, the things that you're starting to notice become a bit less raw in terms of that immediacy. And that's what Burroughs did later in is career too. I mean, some of his earlier books like The Soft Machine have got quite a lot of raw material in them where he was basically cutting stuff up and putting them directly in the text, but later on in the 70s and 80s, he was using it as a compositional tool.

BROOKE: Like a form of editing.

BAKER: Yeah. So he essentially kind of created a bunch of material and used the cut-up. And then from that, all those weird conjunctions would suggest different narratives, different ideas, different characters. So I think putting it back into the process, keep on doing it is the key thing really.

BROOKE: I've never considered that actually.

BAKER: Oh, start cutting up the cut-ups. Yeah, that starts to become really quite strange.

BROOKE: Yeah. Because then maybe you get more of yourself in it, as you were saying.

BAKER: I suppose if you think about the cut-up machine then it can seem quite alienating, because in a sense all you're doing is an almost quasi-mechanical scientific experiment on the text. But I think if you keep on doing it, then consciously and unconsciously, the things you are selecting to cut up start to speak - not with your voice necessarily, but with you. You're guiding the process in a bit more of a conscious way rather than just being this incredibly harsh, brutal way of jamming two things together.

BROOKE: The machine comment is interesting because i think it was Burroughs' grandad who created the adding machine? So I feel like debate over the role of the machine is a common theme in his writing. It's really weird, when I was researching for this, there's this website where you can put stuff in and it cuts it up for you. And I thought 'Burroughs would either love or hate this'.

BAKER: Back in the 90s, when David Bowie was making his album Outside, he used a less sophisticated version of that exact thing. He'd write loads of lyrics, and he's just stick them into this programme and it would cut them all up for him. There's a famous documentary called Cracked Actor where he's seen in Los Angeles completely high on cocaine. But you can see him with scissors and texts, he's cutting up his lyrics. He's doing Burroughs' method.

BROOKE: That's so interesting, I didn't know that. Speaking of different artists, what role do you think spontaneity plays in the career of the artist? Writers, singers and photographers have all said their best work came by accident. There's the famous quote by Leonard Cohen: "If I knew where the good songs came from, I'd go there more often". Is the cut-up a way of artificially producing this?

BAKER: I think it is in a way, yeah. I've been very interested in this for a long time. The idea of the creative flow or 'being in the zone'. I think it's almost like a meditative practise in a way. I think what the cut-up allows you to do is get out of your own way. So the conscious mind which is trying to organise and steer things, you're having to set that aside a little bit. Then other channels are allowed to come through. I think once you're quite deeply involved in that, you can practise it when you're writing without doing cut-ups, you can kind of put yourself in the same place.

BROOKE: Oh, really?

BAKER: So I had the experience in 2023 where I had an image, a dream image, very Burroughsian, and I wrote it down and realised it was going places I didn't understand. It became an 80 page poem. It just kind of came through and all I had to do was get out of my own way just to write this stuff down. So not dictation, just to allow the mental radio to tune in and then not fiddle with it.

BROOKE: That's such a Beat Generation concept as well, just writing immediately and exactly how you feel. And I think that's such a hard thing to learn, or unlearn really.

BAKER: I absolutely agree with you. I think it got a bit fetishized with the Beats, the idea that Kerouac wrote on this big long scroll for On The Road. Because, often things do need editing and everything is a part of the practise and you can't just rely on first thoughts all the time, I don't think. There were other writers at the time, like a poet in San Francisco in the 60s called Jack Spicer, and he did a series of lectures where he talked about poetic composition as receiving radio signals. So there's quite a lot of that in the air around that time, but that's something I'm really interested in with regards to the idea of not relying on a romantic idea of the writer or artist as originator and creator. We have all these materials around us and what the cut-up does is to just make that very explicit.

BROOKE: Right, it's quite a postmodernist idea in that sense. Burroughs said that T. S. Eliot's Wasteland was the first ever cut-up, which is such an interesting comment because a lot of people mark it as the first postmodern poem too.

BAKER: One of the interesting things about that is that Ezra Pound went through Elliot's manuscript and cut loads of stuff out of it. So the form we have is something that's just been edited by somebody else, which is quite funny.

BROOKE: Oh, so it's just layers upon layers of cut-ups.

BAKER: It is, exactly.

BROOKE: Do you think it's possible that there's an even vaster future for the cut-up? I mean, we live in a time where there's this huge online library where you can access any media you like. So what do you see for the future of the form?

BAKER: Yeah, it's an ideal time in a sense to be involved in this kind of process, because the material is so accessible. You know, you don't have to hunt it down. The real thing becomes the selection, because there's so much material. It's about what you choose to put together, whereas in the Beat Hotel in Paris, they had a limited selection of texts to choose from. Whatever American papers they could get and whatever pop novels Burroughs was reading and a couple of scientific manuals or something, or art books. So I think for us, living in a world where all that information is at our fingertips, the cut-up becomes what you decide to put together because that's rarely accidental. There's some kind of guiding thing that you think 'I'll put that together with that', even if you're just picking something off the shelf because you've made a selecting decision already. So I think in a sense it's becoming aware of the relationship between the selection and the practice, because if you're selecting two things which are quite close together then the results don't necessarily work quite as well, because they're not interfering with one another. I did a small visual thing a couple of years ago, which was taking some pages from a book of stories about Sinbad the Sailor. Most of the time he's actually washed up on land because all of his ships sink, and I matched it up with a couple of other things but one of them was this modernist poem by a French poet called Mallarmé, and it's called Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard, meaning A Throw of the Dice will Never Abolish Chance. It's a very strange, abstract text about a captain on a ship which is just about to be washed up on the beach, kind of shipwrecked. So there's a thematic continuity because they're so different that mashing them together was actually pretty productive. But that's one of the interesting things about Burroughs, what he's choosing to put into the machine. Which gives you that really Burroughsian flavour of lots of his language. You can think, 'Oh, I wonder where he's drawing that from?'. Similar with someone like J. G. Ballard, he's not doing it with cut-ups but he's obviously reading lots of scientific manuals in the 60s and 70s or medical books and all of that language enters into his text so you can kind of diagnose where he's getting it from.

BROOKE: That's so interesting. I mean, I've thought long and hard about what the future of the cut-up could be. I don't know if you've possibly seen these edits on TikTok where it's a weird interpretation of the cut-up films. It's random and unrelated videos from films and YouTube videos and then really emotional music on top. It'll be like a monkey scrolling on an iPhone and then a scene from a French New Wave film but when they're put together it does evoke some kind of emotion.

BAKER: That's really interesting. That's almost going back to the early days of cinema and montage cinema where you really are sticking two different things together. And it's the viewer who's doing all the work by trying to jam these things together. And the emotional reaction can be quite strong, as you say. I mean the idea of visual cut-ups has been around for quite a while now, 20 odd years. I think you're right with things like TikTok being able to democratise all of that. So, it's not about, you know, a DJ in a club - everyone can make a mixtape on their laptop now. And I think that's really great.

BROOKE: It's interesting the emphasis you place on selection, especially in relation to the Beat Hotel, which I'm actually visiting soon. I made a copy of Gysin's Dreamachine once. Its really tedious, I had to use what I had and placed it on a record player with a torch underneath. And then you just sit in front of it for a while.

BAKER: Did it have much of an effect?

BROOKE: It did, sort of. But my problem was, you know the new generation, my attention span is not long enough. But it's supposed to, I saw a few colours but you're supposed to sit there until you have visions.

BAKER: Yeah, they both used to do mirror gazing as well, where they'd basically sit in front of a mirror for hours. And they would see weird things in the background or it would show them things, presumably it was their brain starting to really process stuff in a weird way. And I presume it's the same with the Dreamachine. What he's doing is giving you some real strange lighting and your brain is starting to process in a really curious way there. I don't necessarily believe these are magical and all that kind of stuff. But I do think it's a kind of quasi-psychedelic kind of experience. But instead of using narcotics, it was using light shows.

BROOKE: Well, maybe the drugs too.

BAKER: Yeah, in that sense Burroughs was not particularly well. For him it was mainly heroin, of course, and derivatives thereof. He did have a quest in the 50s, a film has just been made actually called Queer , where he goes on this quest to find this ultimate peyote which makes you have all these visions.

BROOKE: Oh yeah, I'm dying to see it.

BAKER: But I think he became less and less interested in psychedelics and yeah, heroin became his thing. Where he's just sit and stare at his toe for eight hours at a time, you know?

BROOKE: Oh God, I remember reading Naked Lunch when I was 14 and I was like 'Oh my god, I'm never touching that'. I mean, the description is just so disgusting.

BAKER: That's funny because when I was 14, weirdly, they had some Burroughs in my local library. They had Cities of the Red Night, and I read that but Naked Lunch was out of print for years and years. I didn't buy it until it was reprinted in the late 1980s when I went to a university campus for an interview and they had it in a bookshop. I thought, 'Oh my god, Naked Lunch'. And so I got a copy then. And I remember talking to a lecturer at an interview day and it was actually someone who had been his own PhD supervisor, a guy called Eric Mottram who'd written the first book about Burroughs. So I talked to him about Burroughs and he asked me about Naked Lunch and I told him it wasn't in print. And he was really, really surprised. But that's what you're saying, now all these things are completely available whereas then, I just couldn't get hold of it. There was no way of getting it, no eBay to look on to try and get a hold of a copy.

BROOKE: That's crazy to me. And the Beats were really passionate about all texts being readily available. I think Burroughs would applaud how far the cut-up method has come. So, what would your advice be to readers who will be enacting the cut-up method themselves? Is there a balance to be found between spontaneity and carefully selected words?

BAKER: I think the first thing is, selection comes first. And having a variety of material is the really interesting thing, and not to be too narrow in your range. Because I think the more narrow you are in terms of the kind of set of materials you've got, the less the conjunctions are going to be unusual because they're going to share too much in terms of a linguistic register or discourse or whatever it might be. So, having scientific textbooks and stuff like that, they're wonderful for cutting up, get a hold of one of those in a second hand bookshop. And then stick that with a pulp novel, pop romance and a fancy novel or a science fiction novel, and a couple of newspapers. That gives you plenty of materials to just kind of jam together and then you get all kinds of strange things. First is select a real broad range. And then you literally get your scissors out and just start. You start playing around with it and go really basic, you know, get some paper and some Pritt stick and scissors and see what comes out. But keep going, because I think with cut-ups you don't really hit the nail on the hammer the first few tries. Sometimes you'll think 'this is a bit rubbish', it doesn't really work, but you have to keep going and trying it. But once you've got that body of cut-ups, don't stop there. Start cutting up the cut-ups.

Leave a comment